Hopefully we can get a field to attract a significant other

Added with golden ratio facial stracture would be perfect

@JAAJ you might need to use cone of power to make it happen for real lol

You can send SammyG a message and he will send you the invoice for paypal to pay and the field

I like it! Would work like the energetic apparel! Except for bed sheets and stuff

Maybe it was a different time line… But wasn’t there a bed sheet like that before? Provided protection or something?

I forget…

I would definitely buy after the wave of NFTs are over!

I don’t know @IAmJonathan , maybe before I discover sapien ![]()

There used to be a fleece blanket on sale that…

would make u seem sorta camoflaged. So that U wouldnt be noticed or maybe less noticed by entities.

(Dont quote me on my wording.) I cant remember what I ate today, but I remember the fleece blanket, lol.

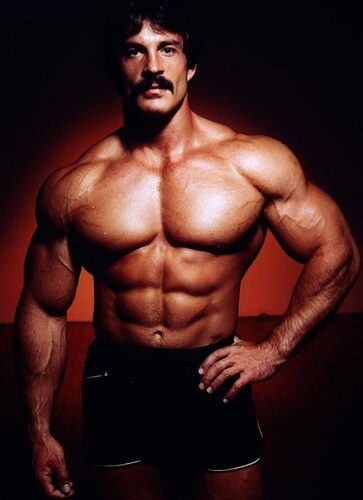

some suggestions in regards to male body looks

- bigger bone structure

- mesomorph body type

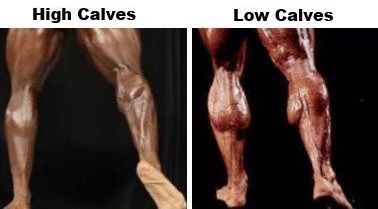

- full muscle insertions

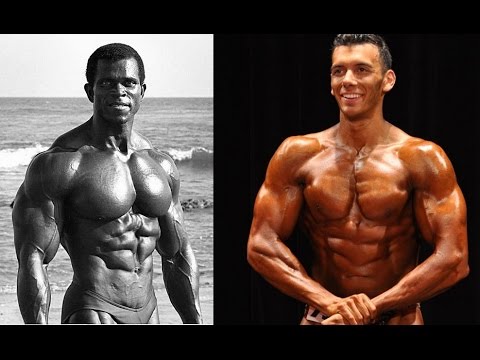

full muscle insertions

the left one has full muscles insertions as well; the right one not, the right one also has a weak body structure and no matter how much muscle he adds imo it will always look weird…

mediocre upper, terrible lower

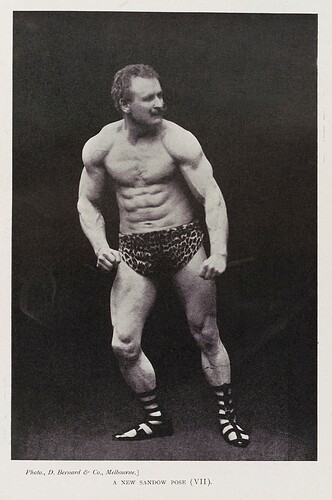

has less muscle than the one above but looks SO MUCH better

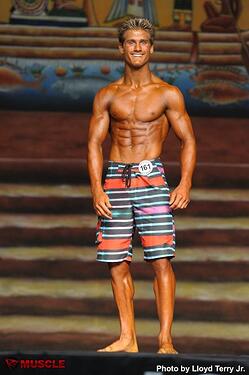

weak petite physique

ectomorph unpleasing physique compared to the first one for example

high bicep insertion, lower insertions look much better

full/long/low muscle insertions

conclusion/solution for all ?

→ male golden ratio bone structure and muscle attachments:

for those that have a small bone structure, it will grow and vice versa. Also for all cases the shape will adapt to more aesthically pleasing (golden ratio !). Same for the muscle insertions.

(user decides himself with or without other fields how big his muscles become, that part is up to him and how much fat he has)

With the caption:

“not pleasing at all”, he needs to develop his traps.

If u look closely u can see the last pic is a fake, the legs have been replaced, lol.

That’s Mr Waves lol second “greatest” men’s physique Mr Olympia

I don’t think his upper body is mediocre at all… He’s bigger than Frank Zane

Maybe it’s the men’s physique posing thats making him look iffy for you (i personally really dislike their posing style, it’s not bodybuilding to me… No art in it)

And although he doesn’t have tom Platz legs… He has a decent set of wheels too… you just can’t see them under those terrible board shorts haha (a big turn off for me when it comes to mens physique)

I’m not a fan of men’s physique at all… But I’ll call it like i see it too, some of these guys can really do some damage in bigger divisions if they bring up their legs and put on a little muscle

But i support your idea man, that field would be the holy grail of aesthetics

Also, it was nice seeing Mike mentzer in your first pic of the post, it caught my attention to see what’s next ![]()

You even got eugene sandow in there, you know bodybuilding ![]()

If you wanna join our gym folks group chat here on the forums let me know bro

![]()

In the meantime Cap has said that Bone Strengthener helps with building a larger frame

Super Discernment / Divine Discernment field

“Discernment is defined as the ability to notice the fine-point details, the ability to judge something well or the ability to understand and comprehend something. Noticing the distinctive details in a painting and understanding what makes art good and bad is an example of discernment.”

I think a field like this could also be very useful for noticing/discerning manipulative behaviors and actions.

charge water (mandala)

A smart detox field!!!

Totally!

if anything you’r making it less likely ![]()

Hydroxycholoquine, monoclonal antibodies and zinc fields if possible.

Angiogenesis field to regenerate all blood vessels/arteries/veins in the body with a bit of clearing of plaque (all throughout body) would be quite nice since we don’t have a field that regenerates broken blood vessels/veins!

Would be nice to have a field like the truth seeker but for ourselves.

I’d love to know if/when I’m fooling myself.