Only speak this potent word and it conjures images — a magical act in and of itself in our supposedly non-magical, scientific age — images of charlatans and frauds bent over primitive flasks and beakers and furnaces and crucibles, inhaling the noxious and toxic fumes of sulfur and mercury, trying by a variety of obscure and murky processes only darkly understood by their practitioners to turn base metals into gold, and going quite mad in the process, its adepts dying insanely young. It is the last gasp of a dying, unscientific, mediaeval age that is desperate for fresh air in an atmosphere choked with vials of vile philters and smoggy, greasy arts and vapors.

For others, it summons depictions of Daoists and Yogis, performing their ancient breathing and inner alchemical techniques in an effort to transmute themselves to attain realization of the self and beyond — even physical immortality and a body completely transmuted into light.

Alchemy.

Only speak the word and one will make a “real” scientist distinctly uncomfortable, perhaps even somewhat belligerent.

For alchemy — in its quest for the Philosopher’s Stone, The Elixir of Life, capable of transmuting base metals into “gold” — with its bewildering array of coded symbols, astrological lore, geometric diagrams and charts, is really a quest to penetrate the deepest secret of the universe; The essence of life and death and to gain power over matter. In this, it is curiously much like modern physics with its own bewildering array of obscure hierophants scratching the coded symbols of higher mathematics on blackboards, working in their own laboratories of arcane equipment, poring over their own charts of computer-generated models and geometries of atoms, paying enormous sums for obscure volumes of wisdom and recipes of equations, all in aid of its own quest to confect exotic matter, a dark materia prima, able to manipulate the fabric of space-time itself.

And like alchemy, it seeks the patronage of the wealthy and caters to the powerful, all the while speaking its own coded language, trying to keep its secrets to itself and away from the great masses of the people.

The Legendary Philosopher’s Stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals into gold. Elixir vitae, “elixir of life,” also known as the Elixir of Immortality was given to the substance that would indefinitely prolong life, grant eternal life and/or eternal youth that was believed to be allied and sometimes equated with the actual the Philosopher’s Stone, or as a byproduct of its alchemical process.

The possibility that the elixir could prolong life was undoubtedly one of the the chief reasons alchemists continued their search. The aged alchemist, weary with his quest for gold, craved the boon of youth and desired renewed health and strength to assist him in carrying out his great purpose. Not only that, the Elixir was said to be a panacea that cured all diseases and maladies. The alchemist’s quest to complete his “Great Work” was the most sought-after goal. In the view of spiritual alchemy, the making of the Philosopher’s Stone would bring enlightenment upon the maker and conclude this “Great Work”.

Rebis was also known to be the Philosopher’s Stone of the hermeticists and alchemists. It symbolizes the search for unity, androgyny, unity of opposites, wholeness, as well as enlightenment and finding the center. This is the unity of the Sun and Moon, male and female, king and queen, sulfur and mercury. Rebis is a balanced trinity, it is both Mars the male, Venus the female (as loving spouses in a happy marriage are one flesh), and their child, copulating in himself with his parents.

Occultists and magicians became interested in the fantasy material because it was described as an elixir (or powder) by which enlightenment is achieved. Magisterium endowed one with wisdom, revealed secret abilities, and helped one achieve recognition, fame, and renown. This is that spiritual, divine, that is hidden inside each person. Therefore, having set out on the path of enlightenment and self-development, there is a chance to find the mysterious “material”.

It embodies the energy of the spoken word. Alchemists took this idea from the Gnostics, identifying Mercury with the principles of mobility and transformation. Mercury is the archetype of self-conversion/ transformation. The stone is associated with the god Mercury himself. The dual nature of Mercury is determined by its proximity to the male planet - the Sun. Like the Greek Hecate (a personification of the sinful side of the feminine and the moon), known in Roman mythology as Trivia, the goddess of three roads, he was often depicted as three-faced. It also corresponds to the note E in the semitone scale.

The Philosopher’s Stone, the White Stone by the River, The Sword in the Stone, all the same, meaning that which contains the knowledge of creation, a symbol that represents the final outcome of man’s inner transformation, of the conversion of the base metal of his outer character to the golden properties of his higher self. It is all about the evolution of consciousness in the alchemy of time.

NFT Attributes

We initially had quite the list of features and benefits “attached” to the Philosopher’s Stone when we presented it to Captain. However, through his wisdom, we were told these additions would only limit the Stone itself. Therefore, we asked our Captain to make it as powerful and epic as possible without any limitations.

It is the True Philosopher’s Stone. The core concepts and ideas used to facilitate its creation:

Philosopher’s Stone → Vast rapid spiritual growth

and

Elixir of Life (It is a part of the Stone itself) → Pristine health, Immortality, panacea from all diseases and maladiesIt is also a smart field.

The properties of the Philosopher’s Stone can also be directed:

One can also use it an a variety of ways, such as to charge chakras.

Caveat

The subject matter of alchemy is cavernous — therefore the following information presented below may not be 100% correct, however, they are presented to provide some background information, history and context to those unfamiliar with the alchemy in general.

The Origins and Heyday of Alchemy

The Real Significance of Alchemy for Esoteric History

To put it succinctly, the very existence of alchemy is testament to the fact that, from the death of the last great Neoplatonist magician, Iamblichus, to the rise of the Renaissance with its own strong esoteric preoccupations, there was more or less a continuous underground current of esoteric thought deliberately trying to “turn the stream” and to recover ancient lost science. Alchemy was thought to be both the means of recovering that lost science and also the embodiment of it.

Most scholars of alchemy are agreed that its origins lie in ancient Egypt. The English scholar E.J. Holmyard, however, expressed a more cautious outlook toward the view that would connect the science too exclusively with Egypt itself:

The word alchemy is derived from the Arabic name of the art, alkimia, in which ‘al’ is the definite article. On the origin of ‘kimia’ there are differences of opinion. Some hold that it is derived from kmt or chem, the ancient Egyptians’ name for their country; this means ‘the black land,’ and is a reference to the black alluvial soil bordering the Nile as opposed to the tawny-coloured desert sands. In the early days of alchemy it was much practised in Egypt, and if this derivation is accepted the name would mean ‘the Egyptian art.’ Against this etymology is the fact that in ancient texts kmt or chem is never associated with alchemy, and it is perhaps more likely that kimia comes from the Greek chyma, meaning to fuse or cast a metal.

Thus, while the etymology of the word is suggestively obscure, there is little doubt that the actual practice of the art is connected to Egypt in some form.

This becomes more apparent as one searches for the earliest mentions of the art. And in this search for the earliest mention, another strange twist is added to the story, for a new contender for the origin of the practice enters the scene: China.

There is some doubt concerning the earliest mention of alchemy, for a reference to it occurs in a Chinese edict of 44 B.C., while a book on alchemical matters was written in Egypt by Bolos Democritos at a date that cannot be more precisely fixed than about 200 B.C. However, whether the honour should go to China, or whether Egypt established a slight lead, there is no uncertainty about the fact that the main line of development of alchemy began in Hellenistic Egypt, and particularly Alexandria and other towns of the Nile delta.

That both Egypt and China should record some of the earliest mentions of alchemy highlights once again the possibility that the art may be very ancient indeed, and stem from some hitherto unknown contact between the two civilizations, or alternatively, may be the declined legacy in each case of an even older common civilization, of extreme antiquity, from which Egypt and China derived it.

In any case, by the time of the famous Greek alchemist Zosimos of Panopolis, or Akhmim, in Egypt in 300 A.D. “alchemical speculation (had run) riot.”

We now find in it a bewildering confusion of Egyptian magic, Greek philosophy, Gnosticism, Neo-Platonism, Babylonian astrology, Christian theology, and pagan mythology, together with the enigmatical and allusive language that makes the interpretation of alchemical literature so difficult and so uncertain.

By the time of the Byzantine alchemist Stephanos of Alexandria, active during the reign of the Emperor Heraclius I (610–641), alchemy had considerably toned down the Gnostic and Neoplatonic elements, but the situation in general remained more or less the same as far as the confusion and ambiguity present in alchemical texts and their “technological” vocabulary were concerned.

By the time of alchemy’s heyday, “from about A.D. 800 to the middle of the seventeenth century,” its practitioners included everyone from

kings, popes, and emperors to minor clergy, parish clerks, smiths, dyers, and tinkers. Even such accomplished men as Roger Bacon, St Thomas Aquinas, Sir Thomas Browne, John Evelyn, and Sir Isaac Newton were deeply interested in it, and Charles II had an alchemical laboratory built under the royal bedchamber with access by a private staircase. Other alchemical monarchs were Herakleios I of Byzantium, James IV of Scotland, and the Emperor Rudolf II.

In other words, alchemy had the patronage not only of some popes, but more importantly, of the powerful royal houses of Hapsburg and Stuart, whose own connections to Masonry and other esoteric societies and doctrines is a matter of some record.

Exoteric and Esoteric Alchemy - What exactly is alchemy then?

Most people are aware of the fact that alchemy is the “quest to make the Philosophers’ Stone,” and most know that this in turn is a stone which purportedly has the power to “transmute base metals into pure gold,” either through touching them with it, or via some other operation involving it. But here popular knowledge usually stops and fantasy, or ignorance, begins, for all is not as simple as the popular imagination would make it out to be, for the quest for the Philosophers’ Stone really involves the whole system of alchemical belief regarding the properties of matter, and their derivation from the first act of creation itself.

The first thing to be noticed about alchemy is its persistent “dual” nature at almost every level, from the ambiguity of its technical terminology to its overall framework involving both exoteric and esoteric pursuits. In the latter respect, Holmyard observes that:

Alchemy is of a twofold nature, an outward or exoteric and a hidden or esoteric. Exoteric alchemy is concerned with attempts to prepare a substance, the philosophers’ stone, or simply the Stone, endowed with the power of transmuting the base metals lead, tin, copper, iron, and mercury into the precious metals gold and silver… The belief that it could be obtained only by divine grace and favour led to the development of esoteric or mystical alchemy, and this gradually developed into a devotional system where the mundane transmutation of metals became merely symbolic of the transformation of sinful man into a perfect being through prayer and submission to the will of God. The two kinds of alchemy were often inextricably mixed; however, in some of the mystical treatises it is clear that the authors are not concerned with material substances but are employing the language of exoteric alchemy for the sole purpose of expressing theological, philosophical, or mystical beliefs and aspirations. (E.J. Holmyard, Alchemy, pp. 15–16.)

This dual exoteric-esoteric aspect of alchemy, however, is so intricately intertwined that its exoteric aspect “cannot properly be appreciated if the other aspect is not always borne in mind.”

The “dual” aspect of alchemy is replicated in its exoteric practice as well. The mediaeval alchemist Petrus Bonus, writing ca. 1330 A.D., stated that:

The principles of alchemy are twofold, natural and artificial. The natural principles are the causes of the four elements, of the metals, and of all that belongs to them. The artificial principles are sublimation, separation, distillation, calcinations, coagulation, fixation, and creation, besides all the tests, signs, and colours by which the artificer can tell whether these operations have been properly performed or not.

In other words, the operations of alchemy itself constitute the human and artificial element of exoteric alchemy. In this, one sees the connection to the esoteric, for in order to perform these operations, the alchemist himself had to transmute himself, with the aid of divine enlightenment, from the “base metal” of sinful humanity to the “pure gold” of the redeemed and enlightened soul.

The Ambiguous Nature of the Technical Language of Alchemy

Petrus Bonus also notes that the dual aspect of alchemy is further mirrored in its actual technical terminology and style of diction, for everywhere one turns in conventional alchemical texts, one is confronted by intentionally ambiguous language, i.e., language that is intentionally designed to have more than one level of meaning. Even though the actual operations of exoteric alchemy could be transmitted in a very short time, he goes on to explain that the search for that knowledge is very difficult, partly because the adepts use words not only in their ordinary sense but in allegorical, metaphorical, enigmatical, equivocal, and even ironical ways.

In other words, alchemy, like any other occult or esoteric art, used language deliberately designed both to reveal and to conceal. The result, as Holmyard observes, “is that it is not always possible to decide whether a particular passage refers to an actual practical experiment or is of purely esoteric significance.”

Alchemical Operations and Zodiacal Correspondences

This ambiguity may easily be seen by a glance at a typical table of correspondences between alchemical operations and the signs of the zodiac, both of which share common symbols:

Operation <----------------------------> Zodiacal Symbol <----------------------------> Astrological Meaning

Calcination → -------------------------------------- ![]() ---------------------------------- → Aries, the Ram

---------------------------------- → Aries, the Ram

Congelation → ------------------------------------- ![]() ----------------------------------- → Taurus, the Bull

----------------------------------- → Taurus, the Bull

Fixation → ------------------------------------------ ![]() ----------------------------------- → Gemini, the Twins

----------------------------------- → Gemini, the Twins

Solution → ------------------------------------------ ![]() ------------------------------------ → Cancer, the Crab

------------------------------------ → Cancer, the Crab

Digestion → ----------------------------------------- ![]() ------------------------------------ → Leo, the Lion

------------------------------------ → Leo, the Lion

Distillation → ---------------------------------------- ![]() ------------------------------------ → Virgo, the Virgin

------------------------------------ → Virgo, the Virgin

Sublimation → -------------------------------------- ![]() ------------------------------------ → Libra, the Scales

------------------------------------ → Libra, the Scales

Separation → --------------------------------------- ![]() ------------------------------------ → Scorpio, the Scorpion

------------------------------------ → Scorpio, the Scorpion

Ceration → ------------------------------------------ ![]() ------------------------------------ → Sagittarius, the Archer

------------------------------------ → Sagittarius, the Archer

Fermentation → ------------------------------------ ![]() ------------------------------------ → Capricornus, the Goat

------------------------------------ → Capricornus, the Goat

Multiplication → ------------------------------------ ![]() ------------------------------------ → Aquarius, the Water-Bearer

------------------------------------ → Aquarius, the Water-Bearer

Projection → ---------------------------------------- ![]() ------------------------------------ → Pisces, the Fishes

------------------------------------ → Pisces, the Fishes

The point of this table and its true significance becomes increasingly evident, in that alchemy associates certain of its processes and results with the positions of celestial bodies.

Alchemical Base Metals and Planetary Associations

There are also dual uses of some symbols of the common base metals of alchemy that associate them with particular celestial bodies.

Base Metal <----------------------------> Symbol <----------------------------> Celestial body

Gold <----------------------------------------> ʘ <------------------------------------> The Sun

Silver <---------------------------------------> ☽ <------------------------------------> The Moon

Copper <------------------------------------> ![]() <------------------------------------> Venus

<------------------------------------> Venus

Iron <-----------------------------------------> ![]() <------------------------------------> Mars

<------------------------------------> Mars

Mercury <-----------------------------------> ☿ <-------------------------------------> Mercury

Lead <---------------------------------------> ♄ <-------------------------------------> Saturn

Tin <-----------------------------------------> 🜩 <-------------------------------------> Jupiter

This highlights yet another aspect of alchemy’s dualism, and it is a connection to an aspect of the most ancient Egyptian and Sumerian astrology which was its connection of particular planets and celestial bodies with particular crystals and precious gems:

Most modern people only encounter astrology, if they encounter it at all, in the “horoscope” page of the local newspaper, or in little booklets of sun signs in the grocery store aisle. Because of this type of exposure, most people think of astrology as having only to do with the subtle influences of the stars and planets on human life. But there is most decidedly more to the ancient view, as Budge observes:

“The old astrologers believed that precious and semi- precious stones were bearers of the influences of the Seven Astrological Stars or Planets. Thus they associated with the–

“SUN, yellowish or gold-coloured stones, e.g. amber, hyacinth, topaz, chrysolite.

“With the MOON, whitish stones, e.g. the diamond, crystal, opal, beryl, mother-of-pearl.

“With MARS, red stones, e.g. ruby, haematite, jasper, blood-stone.

“With MERCURY, stones of neutral tints, e.g., agate, carnelian, chalcedony, sardonyx.

“With JUPITER, blue stones, e.g. amethyst, turquoise, sapphire, jasper, blue diamond.

“With VENUS, green stones, e.g. the emerald and some kinds of sapphires.

“With SATURN, black stones, e.g. jet, onyx, obsidian, diamond, and black coral.”

As also noted there, while no one really knows the exact origins of astrology, it is known that it was present from the inceptions of the “sciences” of the most advanced civilizations of antiquity: Egypt and Sumer. In particular, it is from Sumeria that most contemporary Western astrology stems, for the Sumerians recorded their astronomical and astrological observations on clay tablets. These

they then interpreted from a magical and not astronomical point of view, and these observations and their comments on them, and interpretations of them, have formed the foundations of the astrology in use in the world for the last 5,000 years. (Budge, op. cit., p. 406.)

But that was not all that was claimed for astrology. Budge continues:

According to ancient traditions preserved by Greek writers, the Babylonians made these observations for some hundreds of thousands of years, and though we must reject such fabulous statements, we are bound to believe that the period during which observations of the heavens were made on the plains of Babylonia comprised many thousands of years.

There is ample evidence to suggest, however, that such views were declined scientific legacies of a much more ancient, and much more sophisticated, civilization. It is thus not outside the bounds of possibility that, indeed, Sumerian astrology has origins that date back “some hundreds of thousands of years.”

So one is presented with an interesting picture: on the one hand, from Egypt and Sumer, one encounters the association of planets and stars with certain crystals and their color properties, that is to say, with certain electromagnetic and spectrographical properties, and on the other hand, from alchemy, one has the association of the same celestial bodies not only with certain types of alchemical operations but with certain types of metals as well. And metals, as everyone knows, have, like crystals, their own unique “lattice” properties of molecular bonding. In short, one has, from two distinct types of esoteric arts, the association of celestial bodies, with certain materials that in turn possess certain lattice and spectrographical properties. This will become a crucial key into prying open yet another aspect of a paleoancient and very sophisticated physics that may once have underlay the declined astrological and alchemical legacies of Sumer and Egypt.

So why associate materials with celestial bodies to begin with? Why should the exoteric and esoteric aspects have come to be intertwined in the first place? Why is there such an association of alchemy and astrology?

The Goal and Quest of Alchemy: The Transmutative Medium of the Materia Prima

The answer to these questions lies once again in the Egyptian roots of alchemy and in what those roots in turn imply. The basic Egyptian view of creation, as pointed out by the celebrated esotericist and “alternative Egyptologist,” René Schwaller De Lubicz, was that all of the existing diversity of the universe stemmed from one underlying “prime matter” or materia prima, an absolutely undifferentiated substrate, an “aether” or medium which then began to undergo differentiation. This initial process of “hyper- differentiation” of an undifferentiated medium Schwaller called the “primary scission.” Further differentiations are in turn performed upon these initial derivations from the medium, until at last the entire diversity of creation arises. While all this sounds rather fanciful, it is in fact capable of a profoundly sophisticated interpretation from the point of view of certain aspects of modern physics, for an absolutely undifferentiated substrate in fact is physically non-observable; it is therefore, as far as physics is concerned, a nothing, even though it may be said that this materia prima has some sort of “existence.” The whole of Egyptian religion and magical practice, then, stem from this viewpoint, for if all arises from this materia prima, then everything that exists, by dint of its existence, can be described in terms of its “topological descent” from that substrate. In short, every existing thing is connected with every other existing thing by virtue of its creation from the same underlying “stuff” or substrate. The substrate exists in every thing, since every thing is but a particular differentiated manifestation of that substrate.

Consequently, this underlying substrate or medium was transmutative in its very nature; it was, so to speak, a “pure potential,” capable of undergoing differentiation and diversification. To put it succinctly, the medium was the Philosophers’ Stone par excellence. Moreover, since it was an undifferentiated medium, it was above the concepts of space and time themselves. It was, in a word, non-local. And hence one can see the connection to Egyptian sympathetic magic and alchemical practice, for if everything is connected via this non-local medium, then one could manipulate and influence another object (or person!) via the medium from which they are descended. This was supposedly accomplished by reconstructing as exact an analogue of that object’s “descent” or process of differentiation from the medium itself. One had, so to speak, to “back engineer” the whole process of differentiations.

And with this, one perceives the connection to alchemy, to what its real goal was, and to why it connected the exoteric and esoteric aspects of its practice, for if the exoteric operations were to work, the operator performing them had himself to ascend back up the path of his own differentiation and “topological descent” from that medium, at least, insofar as it was possible for him to do so. The quest of alchemy, in short, was to literally embody that materia prima and its transmutative powers as fully within lower diversified matter as was possible in the earthly Philosophers’ Stone.

These views of the underlying substrate or materia prima persisted into the Hellenic philosophers, and became, via Aristotle, the common currency of later occidental alchemy. For Aristotle,

The basis of the material world was a prime or primitive matter, which had, however, only a potential existence, until impressed by ‘form.’ By form he did not mean shape only, but all that conferred upon a body its specific properties.

In terms of the topological metaphor of alchemy, in other words, Aristotle’s “form” is the Egyptians’ “primary scission” with all its ensuing “differentiations.”

This view of the materia prima and the topological descents and differentiations of existing things is the real basis of the famous alchemical and esoteric axiom “as above, so below.” In fact, in the most prized and famous alchemical text, the Emerald Tablet of Thoth, this axiom of the transmutative medium found its most famous expression:

True it is, without falsehood, certain and most true. That which is above is like to that which is below, and that which is below is like to that which is above, to accomplish the miracles of one thing.

And as all things were by the contemplation of one, so all things arose from this one thing by a single act of adaptation.

In the last sentence of the above quotation, one may see encapsulated the whole sum and substance of alchemical “physics”: the “one thing” is the undifferentiated substrate, the “arising” of all things from that substrate is the primary scission, and the “single act of adaptation” that occurs “by the contemplation of one” is the act of differentiation itself, brought about by Intelligence and a supreme act of will. It will be noted that the act of differentiation thus also connotes placing the undifferentiated medium, which is in a state of utter equilibrium, into a more or less constant state of non- equilibrium or stress.

With this understanding of the ancient view of the transmutative medium in hand — a view that is decidedly modern once all the residue of metaphysics is boiled out of it — one is finally in a position to assess alchemical accounts of the quest for and composition of the Philosophers’ Stone. From the act of that initial “differentiation” of the underlying materia prima, one ends up with three entities: 1) the underlying medium itself, 2) the differentiated parts of it, and 3) their common properties. Interestingly enough, this tripartite structure becomes one of the properties of the Philosophers’ Stone itself, in some alchemical texts, for it is often referred to as the “tripartite Stone.” For example,

According to an anonymous seventeenth-century book entitled The Sophic Hydrolith, the Philosophers’ Stone, or the ancient secret, incomprehensible, heavenly, blessed, and triune universal stone of the sages, is made from a kind of mineral by grinding it to powder, resolving it into its three elements, and recombining these elements into a solid stoneof the fusibility of wax.

Note here that there are three essential operations to the successful confection of this “triune universal stone”:

- Subjecting it to stress (“grinding it to powder”);

- Recapitulating the process of differentiation (“resolving it into its three elements”); and

- “Reverse engineering” its original topological descent from the medium (“recombining these elements into a solid stone”).

The direct connection of the Philosophers’ Stone to the underlying transmutative materia prima is made even more apparent in the following passage from the fourteenth-century alchemist, Peter Bonus:

In the first sense our Stone is the leaven of all other metals, and changes them into its own nature — a small piece of leaven leavening a whole lump. As leaven, though of the same nature with dough, cannot raise it until, from being dough, it has received a new quality which it did not possess before, so our Stone cannot change metals until it is changed itself, and has added to it a certain virtue which it did not possess before. It cannot change, or colour, unless it has first itself been changed and coloured. Ordinary leaven receives its fermenting power through the digestive virtue of gentle and hidden heat; and so our Stone is rendered capable of fermenting, converting, and altering metals by means of a certain digestive heat, which brings out its potential and latent properties, seeing that without heat neither digestion nor operation is possible.

This is a very revealing passage, and for several reasons.

We have the following assertions by Bonus:

-

The Philosophers’ Stone is “the leaven of all other metals,” in other words, the “leaven” metaphor is employed to denote the fact that in some sense the Philosophers’ Stone partakes of the properties of the underlying transmutative medium directly: as leaven is present throughout a whole mass of dough, so the medium is present throughout all the differentiations of created things within it, and that are comprised of it. That medium has, so to speak, literally been “em-bodied” within the Philosophers’ Stone, a metaphor that, as we shall shortly see, Bonus himself employs;

-

The Philosophers’ Stone can effect no change or transmutation until it itself has undergone change and transmutation. This is most likely to be understood in connection with the first point immediately above. But note also that the ability to change is connected with color. As we shall see, this reference to color will assume great significance as a sign of a genuinely alchemical transmutation, even for modern physics;

-

This change in turn is accomplished by heat, for “our Stone is rendered capable of fermenting, converting, and altering metals by means of a certain digestive heat, which brings out its potential and latent properties.”

Thus, the Philosophers’ Stone is confected by:

- Heat, or, once again, a stress, which makes it undergo a

- Change, or once again, differentiation which “Brings out its potential and latent properties,” which are those of

- The transmutative medium itself.

In other words, some of the properties of that transmutative medium are literally “em-bodied” in the Philosophers’ Stone by dint of some process involving heat and color.

Bonus expands on this “embodiment” metaphor by drawing an analogy to the body and the soul as follows:

It is the body which retains the soul, and the soul can shew its power only when it is united to the body. Therefore when the artist sees the white soul arise, he should join it to its body in the same instant, for no soul can be retained without its body. This union takes place through the mediation of the spirit, for the soul cannot abide in the body except through the spirit, which gives permanence to their union, and this conjunction is the end of the work. Now, the body is nothing new or foreign; but that which was before hidden becomes manifest and that which was manifest becomes hidden. The body is stronger than soul and spirit, and if they are to be retained it must be by means of the body. The body is the form, and the ferment, and the Tincture of which the sages are in search. It is white actually and red potentially; while it is white it is still imperfect, but it is perfected when it becomes red.

In typical fashion, Bonus both reveals, and conceals, much about the Philosophers’ Stone in this passage.

We may summarize these points in connection with the italicized portions of the quotation just cited.

-

Note first of all that the Stone is now a “tincture,” implying that it is not a “stone” at all, but a liquid;

-

Observe the important use made of the “body-soul” analogy to “em-body” something. In this case, it is rather clear what Bonus means: the transmutative properties of the medium itself are the “soul,” which requires a “body,” the Stone itself, through which to work. In his own words, it is “this conjunction” that “is the end of the work” or its goal.

-

Thus, the “body” or material that undergoes the change and acquires its new transmutative properties is “nothing new or foreign,” i.e., it remains what it was before in terms of its being a mineral. But…

-

… some “hidden” properties have now become “manifest.” This cryptic remark can be explained by reference to the transmutative medium once again. As was previously mentioned, everything differentiated from that medium inevitably retains to varying degrees the transmutative properties of that medium by virtue of their descent from it. Thus, in alchemical thinking, these properties remain latent in any substance, particularly in its “pure” or alchemically “refined” form. Thus, the goal of the operations of exoteric alchemy is to make these hidden and latent properties manifest; it is to sharpen or intensify the latent properties of the transmutative medium that remain in any element. Thus, the alchemist is really seeking an altered state of ordinary matter, so that the “body” can become, in Bonus’ words, “the form, and the ferment, and the Tincture of which the sages are in search,” that is, so that “ordinary matter” can embody the transmutative properties of the medium itself in this world.

-

And finally, we have a most important clue from Bonus: there is a distinct spectrographic sequence of colors that allows the alchemist to know when he is getting “close”: in its manifest form it is “white actually,” and when processed through its final stage of refinement to bring out its latent potential, it is “red potentially.” Thus, “while it is white it is still imperfect, but it is perfected when it becomes red.”

White, and red.

These are the two colors that we shall see recur over and over again.

Thus, the whole goal of the alchemical art lay in “the general idea that the powers of the cosmic soul must somehow be concentrated in a solid, the philosophers’ stone or elixir, which would then be able

to carry out the transmutations that the alchemists desired.” It was an attempt to reconstruct, for specific cases, the descent of specific minerals from that undifferentiated “cosmic soul” or medium as exactly as possible, in order to incorporate that “cosmic soul’s” very powers of transmutation in ordinary matter. As Holmyard states it, “The underlying idea seems to have been that since the prime matter was the same in all substances, an approximation to this prime matter should be the first quest of alchemy.” The ability to confect such a “philosophical gold” would indeed give its possessors an awesome power.

In addition, there is yet another esoteric connection to alchemy and this quest to confect the Philosophers’ Stone, and we have already encountered it: the Emerald Tablet of Thoth, or, in his Hellenistic incarnation, Hermes Trismegistus, the Thrice Great Hermes, the grand magister of alchemy, the patron of all alchemical adepts. By its constant reference to the Emerald Tablet, alchemy itself acknowledges that the goal of its craft is precisely the reconstitution of this ancient, lost power, the power to manipulate the transmutative medium itself.

The Problem of Alchemy’s Survival: The Triune Stone and the Augustinian Trinity

As was suggested previously, alchemy was the principal mechanism by which esoteric and occult studies survived in a continuous stream from the death of the last Neoplatonist magician, philosopher, and theurgist — Iamblichus — to the rise of the Templars. As was also suggested, this survival in part depended upon royal, imperial, and even occasionally Lateran patronage.

But there is another mechanism at work in alchemy’s survival during this period, particularly in the Latin Christian West, and it is a rather surprising one, and to understand it, one must understand the strange and strong relationship between the “triune Philosophers’ Stone” and the Christian West’s Augustinized doctrine of the Holy Trinity. To understand it, in other words, one must do a little “theology.” And it may come as a surprise to many people, the doctrine which came to prevail in the mediaeval Latin Church was not the original Christian doctrine of the Trinity, which survived only in the Orthodox Catholic Churches of the East. Indeed, the Eastern Orthodox Churches to this day regard the doctrine that came to prevail throughout the West and even at Rome itself as a formal heresy of the highest order, which played no small role in the formal severing of communion between Rome and Constantinople in 1014, and outright mutual excommunication and schism later in 1054.

While this is not the appropriate place to delve into these issues, an understanding of the resemblance of the Augustinized doctrine of the Christian West is essential to understand the enormity of alchemy’s view of its “triune Philosophers’ Stone.”

Clues to deciphering this strange connection occurs when translating the work of an eastern Patriarch of Constantinople, who, upon learning of the exact content and nature of the formulation of Trinitarian doctrine that was increasingly accepted throughout the Christian West, wrote that the doctrine was more appropriate to a formulation of “sensory things,” and not as a formulation of theological doctrine. In other words, the doctrine of the Trinity as formulated in the Latin West was more appropriate to physics than to theology. It was an echo of other comments one often finds in works of earlier Greek patristic authors addressing similar issues.

This indeed serves as a kind of Rosetta Stone to unlock the possible physics meaning of ancient Hermetic texts, for what this ninth- century Christian patriarch was suggesting was something truly revolutionary: the whole philosophy of Hermeticism and Neoplatonism as outlined in so many texts was less about metaphysics in the standard academic sense, and more about the physics of the underlying medium.

Through this lens, certain Neoplatonic and Hermetic texts could indeed be interpreted as containing nothing but an encoded physics of the materia prima. In doing so, one particular passage from the Hermetica becomes particularly significant. The passage in question was about a “topological metaphor in Hermes Trismegistus’ conception of God, Space, and Kosmos (Θεος, Τομος, Κοσμος).” And in its own very suggestive way, it contained its own insight on the “triune Philosophers’ Stone,” by way of a peculiar metaphor of topological triangulation:

A very different and in some respects more sophisticated version of the metaphor of topological non-equilibrium is found in the Hermetica of Hermes Trismegistus…here an attempt will be made to render the implied topological metaphor of one particular passage formally explicit. This passage is the Libellus II:1-6b, a short dialogue between Hermes and his disciple, Asclepius:

“Of what magnitude then must be that Space in which the Kosmos is moved? And of what nature? Must not that Space be far greater, that it may be able to contain the continuous motion of the Kosmos, and that the thing moved may not be cramped through want of room, and cease to move? — (Asclepius): Great indeed must be that Space, Trismegistus. — (Hermes): And of what nature must it be, Asclepius? Must it not be of opposite nature to Kosmos? And of opposite nature to body is the incorporeal… Space is an object of thought, but not in the same sense that God is, for God is an object of thought primarily to himself, but Space is an object ofthought to us, not to itself.”

This passage thus evidences the type of “ternary” thinking encountered in Plotinus, and a kind of metaphysical and dialectical version of topological triangulation… But there is a notable distinction between Plotinus’ ternary structure, and that of the Hermetica: whereas in Plotinus’ system the three principal objects in view are the One, the Intellect, and the World Soul, here the principal objects in view are the triad of Theos, Topos, and Kosmos (Θεος, Τοπος, Κοσμος), or God, Space, and Kosmos.

So in Hermes’ version of the metaphor, the following “triangulation” occurs, with the terms “God, Space, Kosmos” becoming the names or symbols for each vertex or region.

Since what is being described here are three regions or what topologists would call “neighborhoods,” what is actually being modeled, via this ancient metaphor, is not only a kind of “topological triangulation” but that very triangulation is being accomplished by functional distinctions between each region, each of which is not only a “physical nothing” but more importantly, a differentiated nothing. The physical medium on this ancient model thus creates information, and in so doing, transmutes itself. This conception is the basis, of course, of alchemy.

The resemblance of this Hermetic topological metaphor to the Augustinian Trinitarian shield, with its own dialectics of oppositions between the three divine Persons, will immediately be evident, and this suggests that one of the strongest reasons for alchemy’s survival throughout the Western Middle Ages and beyond is that there was a fertile, widely accepted cultural matrix in which it could thrive, for that supposedly theological doctrine, with its own roots deep in Neoplatonism, and therefore with its own deep but largely unsuspected roots in Egyptian hermeticism, was really about physics and topology in a proper sense.

Alchemical References and Analogues to the Augustinized Trinity

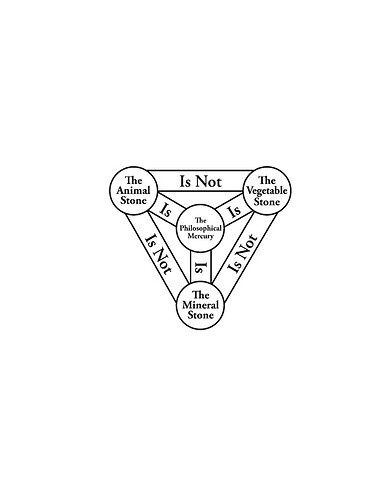

A survey of alchemical references to the “triune Philosophers’ Stone” will only bring the fact of the West’s widespread Neoplatonic and Augustinian cultural matrix, and alchemy’s relationship to it, into even sharper focus. For example, the Rosarium Philosophorum (The Rosary of the Philosophers) refers to the animal, vegetable, and mineral nature of the Philosophers’ Stone, as do many alchemical texts. More importantly, it cites the alchemist Arnoldus as stating “Let the Artificers of Alchemy know this, that the forms of metals cannot be transmuted unless they be reduced to their first matter, and then they are transmuted into another form than that which they had before.” Arnoldus is implying precisely the type of “back- engineering” of matter in its topological descent from the materia prima as being essential to the successful confection of the Philosophers’ Stone.

Similarly, the Rosarium Philosophorum cites an intriguing quotation of Rosinus, in which the doctrinal formularies of the Trinity are very much in evidence:

We use true nature because nature does not amend nature, unless it be into his own nature. There are three principal Stones of Philosophers. That is mineral, animal, and vegetable. A mineral Stone, a vegetable Stone, and an animal Stone, three in name but one in essence. The Spirit is double, that is, tincturing and preparing.

The resonance of this formulary to the standard Trinitarian doctrinal and hymnographical expression — three in persons, one in essence — is astonishing. While there is nothing peculiarly Augustinian about this formulary in and of itself, the last sentence concerning the Spirit being “double” is strongly suggestive of the Augustinian formulation of the Trinity, since in the Augustinian formulation the Spirit is made to take His personal origin from the Father and the Son, as the interpolated version of the Nicene creed in use throughout Western Christianity states, and as a glance at the Trinitarian shield cited previously will disclose. Indeed, so strongly is this idea connected with that formulation that the Augustinian doctrine of the Trinity is sometimes simply referred to as the doctrine of the “double procession” of the Holy Spirit. The alchemical reference is therefore suggestive, but hardly conclusive.

Arnoldus de Nova Villa makes yet another reference to the triune Stone in connection with the Christian Trinity in his Cymicall Treatise:

In the beginning of this labour, I’le [sic] say, that the most excellent Hermes teaches the way in plain words to rationall [sic] men, but in occult and hid speeches to the unwise and fools. I say that the father son and holy ghost are one, and yet three, so speaking of our Stone I say three are one, and yet are divided.

The Trinitarian reference again is quite clear, but again, there is nothing distinctly Augustinian about it. Arnoldus additionally makes the comment that the “unifying substance” of the triune Stone is Mercury, for “out of Mercury is everything made.” This type of reference causes many who are unfamiliar with alchemical texts to misinterpret what is actually being said. The term “mercury” is often used in two senses, the first in its literal prosaic sense, referring to the chemical element itself. The second usage, often coupled with other designators such as “Our Mercury” or “the Philosophical Mercury” in a kind of code name, simply means the underlying transmutative medium or materia prima itself. It is, in short, a code name for the Philosophers’ Stone itself, and for the underlying substance that gives it its power.

In context, then, Arnoldus’ remarks exhibit their character as disguising the “triune Stone” in the context of a strictly Augustinian formulary of the Trinity, since the unity of that Trinity is seen to lie less in the Person of the Father, and more in the impersonal unity of the circle of the divine substance in the middle of the pictogram. Arnoldus is saying much the same thing. The union of the triune Stone in its animal, vegetable, and mineral parts, is the “philosophical Mercury,” the materia prima itself: “the Mercury of the sages,” he says, “is not that common Mercury, call’d by the Philosophers prima materia.” The connection may easily be seen by reproducing the Trinitarian shield and substituting alchemical references for the Trinitarian ones:

The “Alchemical Augustine”: Augustinian Trinitarian Shield with The Triune Stone In the Vertices, and The Philosophical Mercury or Materia Prima As the Unifying Substance

In other words Arnoldus, if one closely scrutinizes his remarks, reproduces the “topological triangulation” we discovered in the much earlier Hermetic texts.

The transmutative medium and materia prima itself receives its own biblical treatment at the hands of some alchemists. For example, Simon Forman interprets the initial creation account of Genesis 1 as an alchemical work, with the primordial waters representing the undifferentiated medium:

Into the darkness then did descend the spirit of God, Upon the watery chaos, whereon he made his abode. Which darkness then was on the face of the deep, In which rested the Chaos, and in it all things asleep. Rude, unformed, without shape, form or any good, Out of which God created all things as it stood… Then out of this Chaos, the four elements were made… The quintessence (that some men it call) Was taken out of the Chaos before the four elements all.

Chaos is the “physical nothing” out of which God fashioned, by differentiating within it, the things of the world. Note also that term “quintessence,” for it will become quite important to the case in part three that alchemy may have formed some of the conceptual basis behind one of physics’ most brilliant, and most unknown, thinkers. Forman expands on what the “quintessence” is in the following manner:

And into every specific thing do put quintessence, To reap such seed thereof; as men do sow, But of themselves. As they are simple and pure in kind.

To put it succinctly, “quintessence” is yet another code name for the Philosopher’s Stone itself, and for the alchemical operation of “embodying” it in a natural substance in order to utilize its powers.

Philippus Theophrastus Areolas Bombastus von Hohenheim, a.k.a. Paracelsus

No survey of alchemy in general nor of alchemy’s peculiar relationship to the Augustinized formulation of the Trinity in the Christian West would be complete without noting the many statements made in its regard by perhaps the most famous and controversial of the late Mediaeval and early Renaissance alchemists, Philippus Theophrastus Areolus Bombastus von Hohenheim, better known as Paracelsus (1493–1541). One gets some measure of the man in the fact that he was born simply “Philippus von Hohenheim” but later took on all the other names himself. Widely noted in his day as an extraordinary physician and alchemist, much of his written output does in fact concern alchemy, and his own disagreements with other practitioners of the craft, no matter how ancient or venerable:

From the middle of this age the Monarchy of all the Arts has been at length derived and conferred on me, Theophrastus Paracelsus, prince of Philosophy and of Medicine. For this purpose I have been chosen by God to extinguish and blot out all the phantasies of elaborate words, be they the words of Aristotle, Galen, Avicenna, Mesva, or the dogmas of any among their followers.

Paracelsus was anything but modest. To drive his point home, he points a definite finger to those whom he regards as the principal corruptors of the ancient craft, and they are the two patrons we have already encountered: “…that sophistical science has to have its ineptitude propped up and fortified by papal and imperial privileges.” Briefly put, Paracelsus knew full well where the main mechanisms that accounted for alchemy’s survival, and corruption, during the Middle Ages ultimately lied.

On the Paleoancient Very High Civilization and Egypt

Part of the uniqueness of Paracelsus is that he was quite aware, and made no secret, of the implications of alchemy for human history and culture. In his book Concerning the Tincture of the Philosophers, he writes that “I have proposed by means of this treatise to disclose to the ignorant and inexperienced: what good arts existed in the first age…” That Paracelsus means by “first age” something predating Egypt and Sumer will become apparanet.

In any case it is to its possession of the secrets of alchemy that Paracelsus ascribes ancient Egypt’s power: “If you do not yet understand from the aforesaid facts, what and how great treasures these are, tell me why no prince or king was ever able to subdue the Egyptians.” But the alchemical science itself he clearly states came from Adam, whom he calls “the first inventor of arts, because he had knowledge of all things as well after the Fall as before.” Because of this plenitude of knowledge, Adam was also able on Paracelsus’ view to predict

the world’s destruction by water. From this cause, too, it came about that his successors erected two tablets of stone, on which they engraved all natural arts in hieroglyphical (sic) characters, in order that their posterity might also become acquainted with this prediction, that so it might be heeded, and provision made in the time of danger. Subsequently, Noah found one of these tables under Mount Araroth, after the Deluge. In this table were described the courses of the upper firmament and of the lower globe, and also of the planets. At length this universal knowledge was divided into several parts, and lessened in its vigour and power. By means of this separation, one man became an astronomer, another a magician, another a cabalist, and a fourth an alchemist. Abraham, that Vulcanic Tubalcain, a consummate astrologer and arithmetician, carried the Art out of the land of Canaan into Egypt, whereupon the Egyptians rose to so great a height and dignity that this wisdom was derived from them by other nations.

Paracelsus makes two very crucial and significant observations here, whose subtle importance may be overlooked since they are so apparently obvious, but only apparently:

-

That alchemy itself is only a fragment of a once larger, highly unified body of knowledge and science that also encompassed astronomy and, for want of a better word, “metaphysics,” or, to put it differently, hyper-dimensional physics, a physics beyond (meta, from the Greek μετα, meaning “beyond”) the ordinary physical and natural world (physics, from the Greek φυσις, meaning “nature” or, in this case, the natural world). In other words, Paracelsus views the Deluge itself as yet another “Tower of Babel Moment” in which an ancient highly unified scientificreligio-philosophical world- view was further fragmented in what could be taken as a classical guerrilla warfare operation, just like the Tower of Babel: massive interference with an enemy’s communications and science and decision-making processes. Paracelsus is, in other words, thoroughly familiar with the esoteric traditions on this point, and more aware than most of their massive implications, for he states them clearly: prior to the high civilizations of classical antiquity — Egypt and Sumer — there was something even higher and much more sophisticated. A little later on Paracelsus even elaborates this concept a bit more fully, attributing the fragmentation of knowledge to the political fragmentation that occurred after the Deluge: “When a son of Noah possessed the third part of the world after the Flood, this Art broke into Chaldaea and Persia, and thence spread into Egypt.”

-

That Egypt gains its knowledge from Sumer, that is, that there is a relationship between the two to that paleoancient Very High Civilization. Paracelsus, of course, disguises this relationship by a “biblical” reference to Abraham and his journey from Ur in Sumer to Canaan, and thence, via his descendants, into Egypt. But of course, the biblical reference is a mere pietism, for Paracelsus cannot have missed the fact that Egypt was already there by the time of their arrival, and cannot have missed the significance of Moses’ growth in the Egyptian royal court. As indicated above, Paracelsus really attributes the further fragmentation of knowledge to the post- flood political fragmentation of the world. He is suggesting, in other words, that the fragmentation of knowledge is threefold: the Chaldaeans (Sumerians) preserving the predominantly astrological and astronomical component, the Hebrews preserving the predominantly Cabalistic component, and the Egyptians preserving the alchemical component. Thus, the “triune Stone” is also a triune Stone of a lost science, fragmented into three scientific and political cultures of the ancient classical world.

Consequently, Paracelsus uses the alchemical symbol of the “triune Stone” as a sigil of his entire philosophy of a hidden history of science and a paleoancient Very High Civilization predating Egypt and Sumer.

On the Relation Between Astronomy and Alchemy

With Paracelsus’ views on ancient history and science in hand, one may more readily appreciate why he not only insists that there are many valid methods to achieving the alchemical goal, but also why he insists upon “the agreement of Astronomy and Alchemy.” Indeed, Paracelsus was to note — with some frustration — that his many attempts to perform the same experiment were sometimes successful, and sometimes not, depending upon the season or other temporal factors. Bear this point in mind, for it will become extraordinarily crucial, for he anticipated, by no less than four centuries, similar observations made meticulously over several years and in several ways, by a brilliant Russian physicist.

Crystals and Metals: Sapphires and Mercury

So precisely does Paracelsus echo some ancient views of space — and anticipate some very modern ones — that some of his words will seem, from any standpoint, ancient or modern, rather remarkable:

To conjure is nothing else than to observe anything rightly, to know and to understand what it is. The crystal is a figure of the air. Whatever appears in the air, movable or immovable, the same appears also in the speculum or crystal as a wave. For the air, the water, and the crystal, so far as vision is concerned are one, like a mirror in which an inverted copy of an object is seen.

At first reading it would appear that Paracelsus is talking about nothing more than eyeglasses and mirrors, and indeed, on one level, he is. Moreover, he is advancing a wave theory of light that at that time is beginning to become part of optical study.

But such a prosaic reading would miss the true significance of his observations, for “air” oftentimes functions, particularly in alchemical literature, as yet another code name for “space” itself, and sometimes even for the materia prima. Consequently, his association of crystals with their implied latticework to air, that is to space itself, implies a very modern, and indeed topological, view of space being advanced by some modern physicists and topologists. Given his familiarity with biblical texts, and his penchant for interpreting them as referring to a lost paleophysics, Paracelsus could hardly have been oblivious to the biblical reference in Ezekiel which seems to refer to space itself as a crystal, as a lattice structure: “And the likeness of the firmament upon the heads of the living creature was as the colour of the terrible crystal, stretched forth over their heads above.”

Paracelsus also, somewhat unusually, couples the idea of crystals and gemstones with metals. Metals, like the more familiar gemstones and crystals, also possess a regular lattice structure, so once again, Paracelsus’ views are, in their own way, very advanced for the day. Most importantly, in yet another rather obscure work, the De Elemente Aquae, Paracelsus states that “in the matter of body and colour the Sapphire is generated from Mercury (the prime principle).” This mention of Sapphire in connection with the philosophical Mercury or materia prima is not without its own contemporary significance, for the former Soviet Union undertook experiments to measure minute fluctuations of the Earth’s gravitational acceleration by means of a large artificial sapphire.

By associating crystals with the Philosophical Mercury and the materia prima and implying that alchemy and the Philosophers’ Stone is a technology with the power to manipulate the latter, Paracelsus is also implying that the lattice structure of crystals and of space itself is intimately related to physical forces.

So what do we have?

Paracelsus has outlined the following ideas:

-

That an ancient and highly unified science was fragmented by various means, including political, as a consequence of the Deluge which he interprets as yet another “Tower of Babel Moment,” and that these fragmentations went, in their astrological-astronomical, cabalistic, and alchemical components to Sumer, the Hebrews, and Egypt, respectively;

-

That some alchemical operations are successfully performed only at certain times and seasons.

-

That there is an intimate relationship between the lattice structure of crystals and metals and the primary transmutative medium itself, implying that lattice structures and physical forces are intimately connected, a very modern idea; and,

-

That there is a metaphysical, or to put it into modern terms, a hyper-dimensional physics component always at work throughout all of the above.

But there’s more, and in uncovering it, we once again see the profound relationship between the Augustinized formulary of the Trinity, its deep and unsuspected roots in ancient Hermeticism (and therefore in an ancient paleophysics), the textual metaphors of topological triangulation in ancient Hermetic texts, and the triune Philosophers’ Stone.

The Augustinized Trinity and Alchemy

The connection begins with Paracelsus’ statement that he “will teach you the tincture, the Arcanum 1, the quintessence, wherein lie hid the foundations of all mysteries and of all works.”

According to Paracelsus, this arcane operation is to be accomplished by means of the Holy Spirit. But once one delves into what he says about this Holy Spirit, one perceives the connection:

This is the Spirit of Truth, which the world cannot comprehend without the interposition of the Holy Ghost, or without the instruction of those who know it. The same is of a mysterious nature, wondrous strength, boundless power. The Saints, from the beginning of the world, have desired to behold its face. By Avicenna this Spirit is named The Soul of the World. For, as the Soul moves in all the limbs of the body, so also does this Spirit move all bodies. And as the Soul is in all the limbs of the Body, so also is this Spirit in all elementary created things.

The reference to the Holy Spirit as an It rather than a fully fledged Person, a Him, is one of those consequences of the Augustinized Trinitarian formulary that began to influence Western Christian piety during the Middle Ages and down to our own day.

But the real clue lies in the identification of the Holy Spirit of Christian doctrine with the World Soul of Neoplatonism, for in the latter conception, this World Soul is made to take its origin from the Intellect, which in turn takes its origin from the One. The World Soul is thus caused by two classes of causes, the Uncaused Cause (the One), and the Caused Cause (the Intellect), much like the Holy Spirit, on the Augustinian formulation, takes His origin from an Uncaused Cause (the Father) and a caused cause (the Son). And note, in the Paracelsan version, it is this World Soul-Holy Spirit that is essential to a purely physical alchemical work. In other words, in Paracelsus’ hands the Augustinized Trinity, which began as was seen in a purely physical and topological metaphor in the Hermetica, and after its peregrinations throughout the Western Middle Ages as a theological doctrine and even as a dialectical interpretation of history itself, ends once again by being reduced back into a purely physics-related phenomenon. No better words can summarize this historical process than the words of Thomas Aquinas himself on the doctrine of the Holy Spirit’s double procession within the Western Trinitarian doctrine, for in the hands of Paracelsus, the historical “cycle has concluded when it returns to the very same substance from which the proceeding began,”

This is made more apparent in the following passage: “Eye hath not seen,” says the alchemical author of the Apocalypse of Hermes, “nor hath ear heard, nor hath the heart of man understood what Heaven hath naturally incorporated with this Spirit.” In other words, once reduced to an It, the “Spirit” becomes merely the sigil for the Philosophers’ Stone itself, and its embodiment into physical matter, into the Stone, which has both physical and metaphysical or hyper-dimensional components. One can see the logic of Paracelsus (and other Western Christian alchemists) at work, for the alchemical work of confecting the Philosophers’ Stone by embodying “the Spirit” into matter is the alchemical analogue to the Incarnation, where the Son becomes incarnate. The Son becomes human, the Spirit becomes the matter of the Stone.

Thus, since this “Spirit”-as-transmutative physical medium is the quintessence of the Philosophers’ Stone, the Stone in turn confers not only longevity and even a kind of immortality, but it is also indestructible.

That Paracelsus seems to be quite knowledgeable of the ultimately Hermetic roots of the Augustinized Trinitarian formulary is made abundantly clear in The Aurora of the Philosophers:

Magic, it is true, had its origin in the Divine Ternary and arose from the Trinity of God. For God marked all His creatures with this Ternary and engraved its hieroglyph on them with His own finger. Nothing in the nature of things can be assigned or produced that lacks this magistery of the Divine Ternary, or that does not even ocularly prove it. The creature teaches us to understand and see the Creator Himself, as St. Paul testifies to the Romans. This covenant of the Divine Ternary, diffused throughout the whole substance of things, is indissoluble. By this, also, we have the secrets of all Nature from the four elements. For the Ternary, with the magical Quaternary, produces a perfect Septenary, endowed with many arcane and demonstrated by things which are known.

Even the reference to the “divine quaternary” has its echo in the Augustinized Trinitarian formulation, for in the Trinitarian shield, one counts not three, but four circles, with the center circle representing the undifferentiated medium, the absolute simplicity, of the divine essence itself, which in the hands of the alchemists, has become a symbol of the Philosophical Mercury, the materia prima itself.

The previous reference to Neoplatonism’s World Soul recalls yet another Neoplatonic theme that enters heavily into alchemical texts, and Paracelsus in particular. This is the doctrine that as all things come from the One, a process called emanation (προοδος in the Greek), so everything returns to It (περιαγωγη). The alchemical text, The Aurora of the Philosophers, having outlined the derivation of all from the Divine Ternary, thus reverses the process:

Here also it refers to the virtues and operations of all creatures, and to their use, since they are stamped and marked with their arcane, signs, characters, and figures, so that there is left in them scarcely the smallest occult point which is not made clear on examination. Then when the Quaternary and the Ternary mount to the Denary is accomplished their retrogression or reduction to unity.

But note that the Neoplatonic metaphor of return occurs in an alchemical context. In other words, the conception of return is itself in turn a metaphor for the alchemical operation of confecting the Philosophers’ Stone, for back-engineering the “topological descent” from the primary physical medium. Paracelsus has seen through all the centuries’ misunderstandings of such metaphysical texts, and their misunderstanding precisely as “philosophical” texts, to the underlying metaphor of a hidden and occulted physics. If this seems a constrained reading of the passage, he himself makes it abundantly clear a little further on:

The Magi in their wisdom asserted that all creatures might be brought to one unified substance…by many industrious and prolonged preparations, exalted and raised up above the range of vegetable substances into mineral, above mineral into metallic, and above perfect metallic substances into a perpetual and divine Quintessence.

Thus, as “emanation” functions as a metaphor for the differentiation of the materia prima giving rise to and accounting for the diversity of creatures, so “return” functions, for the alchemist “in the know,” as a metaphor for the process of “back-engineering” that topological descent in order to confect and embody the medium more immediately itself in a creature, in the Philosophers’ Stone.

Whatever else must be said of Paracelsus, one thing perhaps goes frequently unnoticed. If the old Mediaeval adage be true that “philosophy is the handmaiden of theology,” then Paracelsus has seen through the Augustinized Trinitarian formulary to its ultimately Hermetic roots, and alchemically reduced it once again to its original basis in physics and “sensory things” shorn of the theological associations it subsequently came to hold. With that, he has performed the irrevocable divorce of theology and philosophy as it obtained in the Christian West.

The Ultimate Reductio and the Clincher

If all this is not enough to convince the most resistant skeptic, there is an alchemical text where the identification of the Christian Trinity, in its Augustinzed form, with the topological metaphor of the Hermetica of Hermes Trismegistus is clearly made, and the reduction to physics is accomplished in no uncertain terms. This is a small manuscript entitled simply “Place in Space, the Residence of Motion.” The subtitle of this is even more provocative: “The Secret Mystery of Nature’s progress, being an Elucidation of the Blessed Trinity, Father — Son — and Holy Ghost. Space — Place — and Motion.” Notably, the same sort of functional sets of dialectical oppositions are used to distinguish each vertex as were previously shown in the citations from the Libellus II of the Hermetica of Hermes Trismegistus:

Space, Place, Father & Son are inseparable fixed & immoveable. Motion ye Holy Ghost is that which brings all things to the Blessed determination of the Dei, as in the Floria

Patri, Filii & Spiriti Sancti [sic], etc.

In other words, the Spirit is distinguished by functional opposition — motion — from the Father and the Son, each of whom are symbols of Space and Place. The reduction to physics is once again in evidence.

But there is yet more to the mystery of alchemy…

Stories of Alchemical Success

The persisting mystery of alchemy is precisely its persistence. That is, if the possession of the tremendous powers of the Philosophers’ Stone was the goal of alchemy, why then did no one notice, over the several centuries if not thousands of years of its practice, that no one ever actually did it? How does one account for the persistence of the practice in the face of, presumably, the centuries’ accumulated mountain of failures? Ancient and mediaeval man was no less rational than modern man, and repeated failures would, eventually, have led rational people to abandon the whole enterprise as a futility. How does one account for the persistence of alchemy through the centuries when faced with the enormity, and the likely futility, of its quest to confect the Philosophers’ Stone?

Should not the whole enterprise have been abandoned much sooner than actually was the case? One possibility of explaining this persistence is, of course, that the extremity of the power of the Stone itself was a sufficient motivation to continue pursuing it in spite of the presumably large amount of data that said it could not be done.

But there is another possibility, before which one hesitates, given our inbred modern skepticism concerning all that is “extraordinary.” That possibility is that, on occasion, for whatever reason, there were some successes, that they actually did it. In fact, this is what is actually claimed in the historical record, if one reads such accounts at face value. Only a few of the many examples that Holmyard cites in his book are reproduced here.

- The Swedish General

An intriguing story comes out of eighteenth-century Sweden, when the Scandinavian kingdom was at the height of her power. In 1705 the Swedish general Paykhull

had been convicted of treason and sentenced to death. In an attempt to avert this punishment, he offered the king, Charles XII, a million crowns of gold annually, saying that he could make it alchemically; he claimed to have received the secret from a Polish officer named Lubinski, who had himself obtained it from a Corinthian priest. Charles accepted the offer, and a preliminary test was arranged under the supervision of a British officer, General Hamilton of the Royal Artillery, as an independent observer. All the materials were prepared with great care, in order to prevent the possibility of fraud, then Paykhull added his elixir and a little lead, and a mass of gold resulted which was coined into 147 ducats. A medal struck at the same time bore the inscription (in Latin as usual): ‘O.A. von Paykhull cast this gold by chemical art inStockholm, 1706.”

One has difficulty imagining any alchemical process as being successful. But equally, one has difficulty imagining any king, especially King Charles XII, and a British artillery general, being taken in by a charlatan, especially when the charlatan is on trial for his life, and when Charles XII had potential riches to gain. The Swedish royal courtesans and ministers would have literally hovered over General von Paykhull, scrutinizing his every move.

- A Provincial Frenchman

Another interesting story is mentioned by Holmyard, this time from provincial France, and again, from the early eighteenth century. On this occasion

An ignorant Provencal rustic named Delisle caused a sensation by claiming, with apparent good reason, that he could transform iron and steel into gold. The news came to the ears of the Bishop of Senez, who after witnessing one of Delisle’s experiments wrote to the Minister of State and Comptroller-General of the Treasury in Paris that he could not resist the evidence of his senses. In 1710 Delisle was summoned to Lyons, where, in the presence of the Master of the Lyons Mint, he made much show of distilling some unknown yellow liquid. He then projected two drops of the liquid upon three ounces of pistol bullets fused with saltpeter and alum, and poured the molten mass out on to a piece of iron armour, where it appeared as pure gold, withstanding all tests. The gold thus obtained was coined by the Master of the Mint into medals inscribed Aurum arte Factum, ‘Gold made by Art,’ and these were deposited in the museum at Versailles. Of Delisle’s subsequent life, history has nothing to relate.

Again, we find the association with a Royal government, this time that of France, and in connection with its Treasury and Royal Mint. And again, reason pauses to make us hesitate over the alleged

success. But similarly, reason also forces one to consider that the possibility of a fraud being perpetrated under the watchful eyes of the Master of the Lyon mint is rather slim, especially since the gold that was produced was subjected to “all tests.” Was Delisle’s success the reason for his subsequent disappearance? Or, conversely, did the Versailles Palace, subsequently determining that it had been defrauded, “disappear” Delisle into the bowels of the Bastille? We will never know.

- The Hapsburg Emperors Ferdinand III and Leopold I

One of the best known examples of royal or imperial patronage of alchemical practice was the Holy Roman Hapsburg Emperor Ferdinand III, of which no less than four examples are known. The first concerns an incident in 1647, when an alchemical adept name J.P. Hofmann allegedly successfully performed a transmutation in the presence of Ferdinand himself in the city of Nuremberg.

From this hermetic gold the emperor caused a medal of rare beauty to be struck. It bears on the obverse two shields, in one of which are eight fleursde-lys, and in the other is a crowned lion. The Latin inscriptions signify, ‘The yellow lilies lie down with the snow-white lion; thus the lion will be tamed, thus the yellow lilies will flourish; and that the metal was made by Hofmann. A further inscription reads Tincturae Guttae V Libram, denoting that five drops of the tincture of elixir transmuted a whole pound of the base metal. On the reverse is a central circle with Mars in it, holding the symbol

in one hand and a sword in the other. Around this central circle are six smaller ones, containing the signs of gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, and mercury, with an inscription claiming that in this case the active agent in transmutation was made from iron.

While this is not the last time we shall encounter an alchemical connection to Mars, it is important to note here that once again, the Philosophers’ Stone is not so much an actual stone as it is an elixir or tincture, a liquid.

The next year Ferdinand was at it again, this time in connection with

A certain Richthausen, who claimed to have received the secret of the Art from an adept now dead, (who) performed a transmutation in the presence of the emperor and of the Count von Rutz, director of mines. All precautions against fraud were taken, yet with one grain of the powder provided by Richthausen two and a half pounds of mercury were changed into gold.

Once again, the Emperor Ferdinand had a medallion struck with a value of “300 ducats,” and whose Latin inscription stated that “the Divine Metamorphoses” had been “exhibited at Prague, 15 January 1648, in the presence of his Imperial Majesty Ferdinand III.”

The mysterious Richthausen was active again in 1650, for in that year Ferdinand apparently performed his own transmutation with some of the adept’s powder, and once again struck a medallion indicating that lead had been successfully transformed into gold. The Emperor’s patronage became “official” when, following another successful transmutation in 1658 when Richthausen gave the Elector of Mainz some of the Stone, a transformation of mercury into gold occurred. In gratitude, Ferdinand raised Richthausen to the ranks of the nobility.

Nor did the Hapsburg interest end with Ferdinand. Ferdinand’s son Leopold I was visited in Vienna by an Augustinian monk in 1675, where, again, a “copper vessel” was transmuted into gold, along with some tin. In commemoration of the occasion, gold ducats were struck from the tin. The monk, Wenzel Seyler, had accomplished the whole operation with a powder, for on the obverse of these coins was a bit of poetry:

Aus Wenzel Seyler’s Pulvers Macht

Bin ich von Zinn zu Gold Gemacht.

That is, ‘By the power of Wenzel’s powder I was made into gold from tin.’